- Physics & Mathematics

- Mathematics

A new mathematical equation describes the distribution of different fragment sizes when an object breaks. Remarkably, the distribution is the same for everything from bubbles to spaghetti.

1 Comment Join the conversationWhen you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

From glass ornaments to dry spaghetti, almost everything on Earth that shatters follows certain principles of randomness and entropy, a new study finds.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

From glass ornaments to dry spaghetti, almost everything on Earth that shatters follows certain principles of randomness and entropy, a new study finds.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

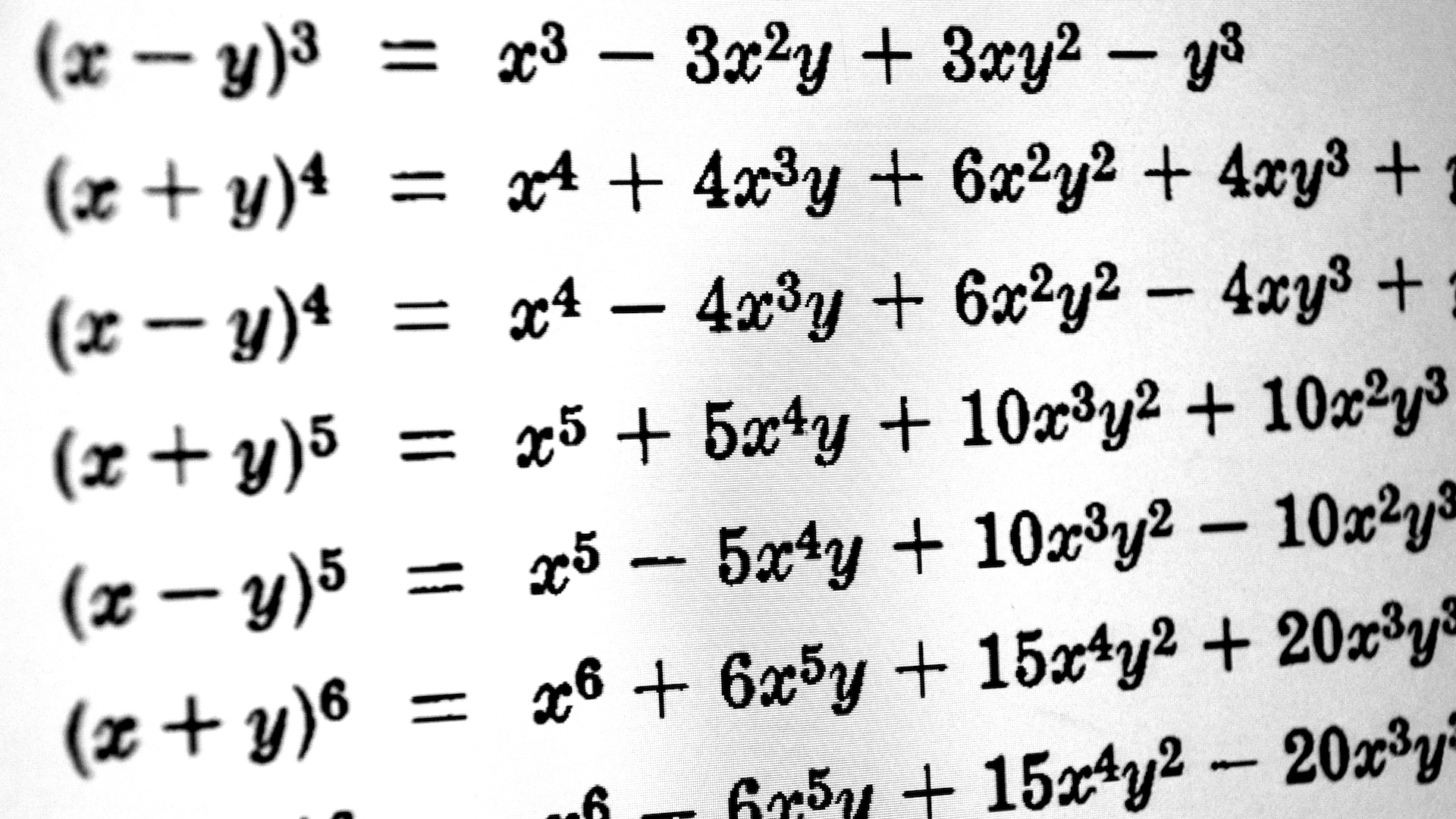

A dropped vase, a crushed sugar cube and an exploding bubble all have something in common: They break apart in similar ways, a new mathematical equation reveals.

A French scientist recently discovered the mathematical equation, which describes the size distribution of fragments that form when something shatters. The equation applies to a variety of materials, including solids, liquids and gas bubbles, according to a new study, published Nov. 26 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Though cracks spread through an object in often unpredictable ways, research has shown that the size distribution of the resulting fragments seems to be consistent, no matter what they're made of — you can always expect a certain ratio of larger fragments to smaller ones. Scientists suspected that this consistency pointed to something universal about the process of fragmenting.

You may like-

Stalagmites adhere to a single mathematical rule, scientists discover

Stalagmites adhere to a single mathematical rule, scientists discover

-

What are the 'magic numbers' in nuclear physics?

What are the 'magic numbers' in nuclear physics?

-

Plants self-organize in a 'hidden order,' echoing pattern found across nature

Plants self-organize in a 'hidden order,' echoing pattern found across nature

Rather than focusing on how fragments form, Emmanuel Villermaux, a physicist at Aix-Marseille University in France, studied the fragments themselves. In the new study, Villermaux argued that fragmenting objects follow the principle of "maximal randomness." This principle suggests that the most likely fragmentation pattern is the messiest one — the one that maximizes entropy, or disorder.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.—400-year-old physics mystery is cracked

—Scientists figured out how to make ceramics that bend and mush instead of shattering

—Frozen droplets explode on camera, for science

Ferenc Kun, a physicist at the University of Debrecen in Hungary, told New Scientist that understanding fragmentation could help scientists determine how energy is spent on shattering ore in industrial mining or how to prepare for rockfalls.

Future work could involve determining the smallest possible size a fragment could have, Villermaux told New Scientist.

It's also possible that the shapes of different fragments could follow a similar relationship, Kun wrote in an accompanying viewpoint article.

Skyler WareSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Skyler WareSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorSkyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Stalagmites adhere to a single mathematical rule, scientists discover

Stalagmites adhere to a single mathematical rule, scientists discover

What are the 'magic numbers' in nuclear physics?

What are the 'magic numbers' in nuclear physics?

Plants self-organize in a 'hidden order,' echoing pattern found across nature

Plants self-organize in a 'hidden order,' echoing pattern found across nature

For the first time, physicists peer inside the nucleus of a molecule using electrons as a probe

For the first time, physicists peer inside the nucleus of a molecule using electrons as a probe

Physicists find a loophole in Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle without breaking it

Physicists find a loophole in Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle without breaking it

Scientists create first-ever visible time crystals using light — and they could one day appear on $100 bills

Latest in Mathematics

Scientists create first-ever visible time crystals using light — and they could one day appear on $100 bills

Latest in Mathematics

Science history: Russian mathematician quietly publishes paper — and solves one of the most famous unsolved conjectures in mathematics — Nov. 11, 2002

Science history: Russian mathematician quietly publishes paper — and solves one of the most famous unsolved conjectures in mathematics — Nov. 11, 2002

Mathematicians discover a completely new way to find prime numbers

Mathematicians discover a completely new way to find prime numbers

'Alien's language' problem that stumped mathematicians for decades may finally be close to a solution

'Alien's language' problem that stumped mathematicians for decades may finally be close to a solution

When was math invented?

When was math invented?

Mathematicians devise new way to solve devilishly difficult algebra equations

Mathematicians devise new way to solve devilishly difficult algebra equations

Mathematicians just solved a 125-year-old problem, uniting 3 theories in physics

Latest in News

Mathematicians just solved a 125-year-old problem, uniting 3 theories in physics

Latest in News

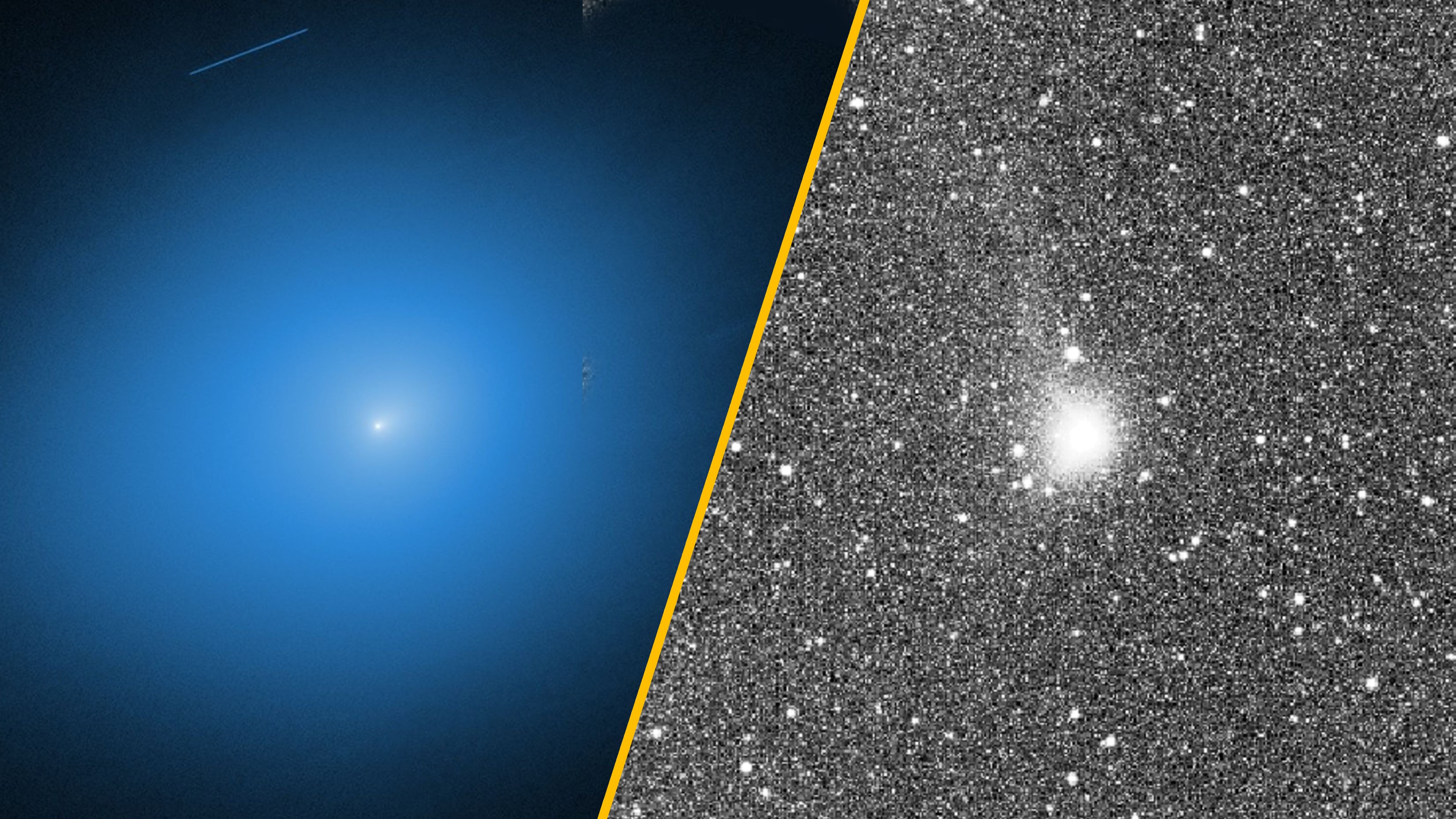

New 3I/ATLAS images show the comet getting active ahead of close encounter with Earth

New 3I/ATLAS images show the comet getting active ahead of close encounter with Earth

Ethereal structure in the sky rivals 'Pillars of Creation' — Space photo of the week

Ethereal structure in the sky rivals 'Pillars of Creation' — Space photo of the week

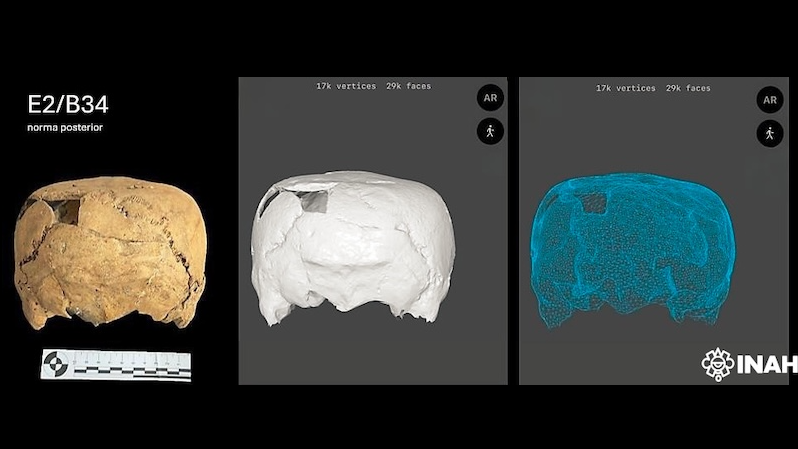

Unusual, 1,400-year-old cube-shaped human skull unearthed in Mexico

Unusual, 1,400-year-old cube-shaped human skull unearthed in Mexico

Strangely bleached rocks on Mars hint that the Red Planet was once a tropical oasis

Strangely bleached rocks on Mars hint that the Red Planet was once a tropical oasis

Lost Indigenous settlements described by Jamestown colonist John Smith finally found

Lost Indigenous settlements described by Jamestown colonist John Smith finally found

2,400-year-old 'sacrificial complex' uncovered in Russia is the richest site of its kind ever discovered

LATEST ARTICLES

2,400-year-old 'sacrificial complex' uncovered in Russia is the richest site of its kind ever discovered

LATEST ARTICLES 1Lost Indigenous settlements described by Jamestown colonist John Smith finally found

1Lost Indigenous settlements described by Jamestown colonist John Smith finally found- 2Strangely bleached rocks on Mars hint that the Red Planet was once a tropical oasis

- 32,400-year-old 'sacrificial complex' uncovered in Russia is the richest site of its kind ever discovered

- 4Ethereal structure in the sky rivals 'Pillars of Creation' — Space photo of the week

- 5What was the loudest sound ever recorded?